After moving to �The Prefabs� at Pen-y-Parc, Five Locks, we started at the �Church School� by Holy Trinity. This consisted of temporary classrooms and the main, stone school, with the toilets separate across the playground. I remember these toilets stank to high heaven in the summer! There was also a playground up against the back wall of the graveyard, and with an access on to Church Road. Although then a very quiet road with relatively few houses, this access was guarded by a metal police man bolted to the wall with his hand up and the sign �Stop!� The other side of the gap, another sign urged us to �Remember Your Kerb Drill!� No namby pamby civilianised Green Cross Code then; this was only a decade after the end of the War!

.. Church School ..

Most play took place in the playground by the graveyard, and a popular pastime was climbing up on to the wall to watch funerals take place. Other times we would look around the gravestones, being very wary of the Bumford crypt which, we convinced ourselves, was haunted. The playground itself was tarmac and the wall rough stone, so there were often scrapes and cuts. One time, one of the pupils started bullying me, so I lost my temper with him and pushed him against the wall, grazing his arm. He never bothered me again, and never �grassed me up�.

It was here we started to learn to read and write, teachers writing up words on the blackboards (chalk boards) with squeaky, screeching chalk for us to copy down in our work books. Classrooms were heated by big coke stoves in the middle of the room and screened off by fire guards, all very cosy. In the summer, on hot days, the classroom doors would be opened. To fuel the stoves, there was a large pile of coke round the back, and we were expressly forbidden to �play on the coke�. One day, I was summoned to the headmistress to be told off for this offence. As I had never been on it, I protested my innocence, which only made things worse; I had been seen there. What actually happened was that my twin brother had been seen on the coke and although we are not identical twins, we were often confused for each other. So I spent the lunch break stood in a corner in a classroom to watch the others playing happily outside, seething with anger and the injustice of it.

The big event of the year was the Christmas Party. For this, children would fetch their own crockery and cutlery, and mothers would produce the cakes, sandwiches, jellies etc.

The only teacher I can remember is the elder Miss Bees (whose sister taught at the nearby West Pontnewydd Junior School, more of which later).

In keeping with much of old Cwmbran and Pontnewydd, where the Church School once stood there is now a housing development.

Then we moved across Church Road to the new, aforementioned Junior School, where my first teacher was Miss Morgan. My only real memory of her is her frustration at her inability to teach me the �times tables� resulting in her making me stand on my chair one day to recite (or attempt to) my tables to the whole class. Not particularly helpful I suppose, but I�ve never borne any malice over it, and I don�t feel psychologically damaged.

.. Mount Pleasant Junior School ..

In the second year, I moved upstairs to Mrs Garrett�s class. Again, the only real memory of this class is her fondness for teaching us needlework � �boys needn�t do needlework � they can do extra arithmetic if they wish�. We all did needlework!

The third year I was with the younger Miss Bees. This was quite an enjoyable year because her emphasis was on English, which I could do, as opposed to arithmetic (God bless Clive Sinclair and his pocket calculator). Of especial pleasure were her weekly vocabulary tests where she would read out words which we had to write down the meanings of, e.g. �saturate� - �to soak or wet right through�.

The final year was spent with Mr Morton, a bit of a martinet, but just the teacher you needed to take you into the 11 Plus. Each class teacher had his or her store cupboard where exercise books, inks and pens etc were kept. Mr Morton also had an earthenware pot full of mercury there, which he would bring out to show us occasionally. There was a big to do one day because someone stole it (the store rooms were never locked), it was never recovered. Imagine today, with Health & Safety, and Control of Hazardous Substances legislation, a teacher keeping his personal �stash� of mercury!

There were again of course, milk breaks in order to fend off rickets. To accompany the free milk, staff used to sell Weston�s (now of course Burton�s) �Jammie Dodger� biscuits. These were loose from large cardboard boxes, and you could get two for a penny (pre-decimal, 12 old pence equalled one shilling, one shilling equalled 5 new pence). These were sold through a window of Miss Morgan�s classroom, by the ramp up to the main entrance. I can still taste the milk, drunk through a mouthful of Jammie Dodger!

Then there were school meals, with the Monday morning ritual of handing in �dinner money� (five shillings � 25p) and getting your name ticked off. This shilling a day bought you a two course meal of varying quality (except the meat, this was always low quality and chiefly gristle) with lots of potatoes to bulk things out. I can well remember having to often chew and chew a piece of meat, sometimes giving up ands surreptitiously putting it back on my plate. On Fridays, the menu was always fried fish in very greasy batter with mashed potatoes and tinned tomatoes. I could only manage the fish if saturated in vinegar. On one occasion we had spring cabbage, dark green and slimy. As a child I always hated cabbage, only acquiring a taste for it in adulthood, so I left it on the side of the plate. An eagle eyed Miss Bees spotted this flagrant waste of good wholesome food, and ordered me to stay at the table until I finished it. I attempted to but failed, so spent the entire lunch break staring with revulsion at this weed on my plate.

St David�s Day was always celebrated, the only concession to Welshness being learning (re-learning each year) the Welsh National anthem in Welsh). The only other Welsh item on the curriculum was again musical, singing �Sospan Bach�. One year I won a book token for my essay on �The Life of St David�; I�ve still got the book I bought with it.

The big event of the year was the school summer fete, with the highlight of the motorised �dragon� coming in for the finale.

Play breaks were always ended by the ringing of a hand bell or the blowing of a whistle. On being summoned back to lessons, we would �parade� by class on the rear playground, then, the �duty teacher� would call us in by classes. One day, it was the normally mild mannered Mr Collier. As we waited patiently, I finished off an apple. Mr Collier saw me, and exploded: �How dare you have the Gaul to eat an apple on parade!� We certainly enjoyed a military style discipline in those days, which served me in good stead in later life - during 35 years in the army I never ate an apple on parade!

Another vivid memory was gathering around the �wireless� with the BBC song books, singing hits like �Bonny Dundee�, �The Song of the Cornish Men� (why did Trelawney have to die?), �Nymphs and Shepherds�, �Morning Has Come� (Night is away, rise with sun�), and many others. Happy days.

Eventually the dreaded 11 Plus loomed, scattering the �cushy� school life for ever. I actually got a �bye� into the second round of the 11 Plus, as I contracted German measles. After some debate as to what to do about this, they decided that as my twin brother had passed the first part, it went without saying that I would have passed it (thank you Lawson), so I just took the second part. I passed, but what if I had failed the first one?

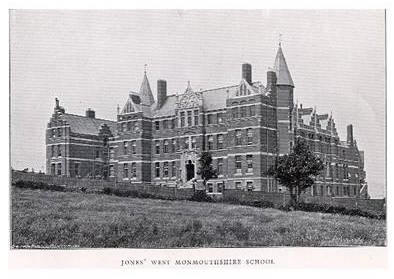

The grammar schools open to Pontnewydd and Cwmbran pupils in those days were Croesyceiliog, West Mon, the former Haberdashers� School in Pontypool, and Abersychan Grammar/Technical School, and there was a preference form to fill in. Most put �Crossy� as first choice, and I was no exception, so imagine my disappointment at being selected for West Mon. Today, I can sincerely say that I was glad to have gone there, a school with a great history and tradition, sadly now existing only as the building.

Of my year, only three of us went to West Mon, Geoffrey Price, Robin Matthews and myself, School life was to be much more serious now.

Prior to starting there was the Visitors� Evening, when new starters and their parents were invited to West Mon for a talk by the headmaster, the diminutive Mr Roy Wiltshire, and a tour of the school and its facilities. And what facilities! Finished in 1898 it nevertheless boasted its own swimming pool, with gymnasium above, a comprehensive art studio with a pottery kiln, and the Science Block which, because it was opened in 1934, was known as �The New Building�. The Old Building was impressive, set atop Blaendare Road, with its gothic turrets and the huge Worshipful Society of Haberdashers Badge on the main entrance, with the motto �Serve and Obey�, and the interior had a quaint charm which appealed to me. At this stage though, I still resented having to travel three miles by bus to school when I could have gone to Crossy. One outcome of this evening was the disappointment of my mother later, who having been shown some pretty impressive furniture made by the pupils � stools with raffia seats, dressing tables etc, somehow expected me to provide them!

At last the First Day dawned as, in September 1962, with my brand new season ticket I waited at the Lowlands bus stop for the bus to Pontypool.

.. Season ticket ..

With butterflies in my stomach I alighted at Pontymoile and went up the hill with streams of other pupils, new and old. It was raining, so my recollection of starting grammar school is of trudging up the hill in my navy raincoat (school approved), Tuf shoes (school approved), and cap perched on my head (�all items of school uniform are available from Fowlers of Pontypool�). Also approved was the grey flannel shirt, �compulsory for First Year pupils�. Gradually, having passed The Lodge where the school caretaker Mr Beard lived, the school emerged from the misty rain, looking like something from a Hammer House of Horror set.

(From a 1930s Boarders� information booklet, prior to the houses being built opposite the school)

After all the necessary admin, we were sorted into classes; at West Mon, classes were W. M & S, with W being the top stream, S the lowest. For the first year however, this was arbitrary since we were all untested. Now, instead of teachers we had �masters�, some of whom still wore black gowns as a badge of office. My form master was Mr Gregory, a junior English master, a very pleasant man.

The First Form classrooms were entered from a balcony overlooking the assembly hall, and we �formed up� for assembly on this balcony. In the main hall, the remainder of the school formed up in ranks across the hall, standing, since until several years later, no seats were brought in. At a given signal, the rear doors would be flung open by prefects, and the command �Open Ranks!� screamed out. On this command, the boys in the centre of the ranks would shuffle left and right to allow a pompous Roy Wiltshire, to strut through the hall, gown flowing behind him, the overall effect being that of Moses parting the Red Sea; as he passed by, the ranks would close in behind him. A couple of years later, when I was down in the hall, as this ritual was being performed, �Roy�s� bald head suddenly turned bright crimson, he shot off to his right and, jumping up to reach, slapped a six foot something Seventh Former across the face, leaving an angry red mark (today that would constitute a Section 47 Assault), and angrily told him off for laughing at him, and to report to his office after assembly, when he would be �taught respect�.

Until 196-? Roman Catholics, of which there were a small number, such as Kieron Pinkey and Jimmy McGivern, were forbidden by Papal Decree, on pain of eternal Damnation, to attend the services of other denominations. Therefore, they would go into 3M�s classroom at the top of the stairs leading into the hall and chat or play chess, how we envied them! Occasionally I would break away and join them, but this was always fraught with danger. Later, a Papal edict removed the terrible punishment of Damnation, and disgruntled, the Catholics were compelled to join us.

On starting at West Mon, you were issued with the School Hymnbook, a small green �English Hymnal�. During assembly, the hymn numbers would be called out �397� (�Cwm Rhondda�) and �657� (�Jerusalem�) being the favourites, guaranteed to produce a rousing response. With its wooden panelling, parquet flooring and stained glass memorial window to Old Boys who fell in the two Wars, overall, the hall was an imposing area.

The most vivid memory of that first academic year is �The Great Freeze� of the winter 1962-63, usually referred to as 1962, but as far as I can remember, it only started in earnest on New Year�s Eve. It certainly was severe, and it carried on to the April. The ancient boiler system very quickly gave up, turning the draughty classrooms into walk-in freezers. Other schools closed down whenever it got too bad, but West Mon, like the Windmill Theatre, never closed. As a concession to the conditions, top coats were allowed to be worn in class, and pupils could suck throat sweets and peppermints in class, Zubes being the favourite, on the recommendation of the senior English master �Chippy� Woods, who appeared to be addicted to them. Frequently, there would be no buses because of the weather, and on several occasions, I walked to school. We had pupils from as far afield as Abertillery and Ponthir (I�ve never worked out why), and these, along with pupils from �up the valley� � Talywain, Pontnewynydd, Garndiffaith, Blaenavon etc, would frequently be released just after lunch, after Red & White and Western Welsh phoned up to warn the school that services to these areas were closing down because of anticipated fresh falls of snow. How we envied them if there was a double period of Maths that afternoon!

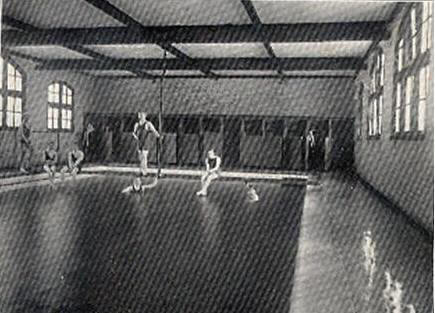

Sport was well provided for, under the supervision of �Max� Horton, the senior sports master who had received a Mention in Dispatches during the War. Naturally, rugby played a large part in the sports curriculum, as �Maxie� would bellow at any boy rash enough to mention football: �THE BALL IS OVAL BOY, OVAL! This didn�t stop the likes of Robin Matthews helping later to develop a successful school football team. But sport wasn�t restricted to rugby, as mentioned there was a swimming pool which, unfortunately, we couldn�t use for the first year as due to a polio outbreak all public pools and baths were closed down.

.. Again, from the 1930s information booklet, hence the quaint bathing costumes! ..

Once the unheated, icy pool re-opened, all swimming was done in the nude. This was because some years before, a boarder had slipped back into the pool after the class had finished, then got his trunks caught on a grating at the bottom of the pool and drowned; rather than modify the grating, it was decided that no trunks meant no catching up on things. Being an all boys school, this didn�t matter too much. Before I finished at West Mon swimming trunks were re-instated.

The gym was very well appointed, with all the usual apparatus, although I always found circuit training tedious.

(Although this is from the same 1930s booklet, it was in as good condition in the 1960s)

Maxie also had us cross country running, although he didn�t join us! One memorable run was out the back of school and up around the Upper Race. Not too bad a run, except that in places we were floundering up to our waists in snow. Miraculously, all returned safely! Summer saw cricket, and in the run up to the school sports day, field and track events, but the real emphasis was always on rugby. This was done either on the field at the back of school, by the Quarry, or down the Skew Field past Pontymoile. The first option involved playing on a steep slope, great for one half, not so good for the other, the second option, clattering in your studs down Blaendare Road, usually on a frosty morning to the Skew field. Down there, a quick knockabout, then back up to school and the unlit, Stygian showers; these definitely needed modernising, which did happen before I left school. I personally never enjoyed rugby, so never became one of the �elite� allowed to wear the school rugby tie, dark blue with gold lions after representing the school at rugby.

In the First Form, French and Latin were the only foreign languages taught, those moving up to 2W or 2M then added German to their curriculum. It was in this first year I developed a lifelong love of foreign languages, spending some twenty two of my thirty five years in the army as a Russian interpreter, with German, French and Serbo-Croat thrown in along the way.

German was taught initially by �Harry� Room, who, deaf from an early age, had originally learned German having never heard it spoken. Thus he spoke very good German, but with a strong Yorkshire accent, which sounded bizarre. He was dependent on an old fashioned hearing aid, so occasionally we would tease him by mouthing words at him. This would cause him to tap the box of his hearing aid, and pull out and check wires. Another jolly jape was to run riot when, on occasions, he would give us some work to get on with, and stand staring out of the window with his earpiece out, oblivious of the pandemonium behind him. Eventually a young graduate arrived as a German master, Olaf Myrhe, of Norwegian descent. He was a very good teacher with outstanding German pronunciation and in the right place at the right time, since on Harry Room�s retirement he became Head of Department. A superb teacher, what he taught me proved extremely useful later in life when I was responsible for a lot of liaison with the West German Army, the Bundeswehr, both from the language and the literature point of view.

During my time we had two assistants, foreign students spending a year at British schools. The first was Herr Peter Hiller, renowned for bringing his guitar in to class and teaching us German songs � who can forget such masterpieces as �Die Affen rasen durch den Wald, und suchen nach dem Kokosnuss � wer hat den Kokosnuss geklaut?�[1] He was also given a role in the school play, �Julius Caesar� when, for one performance, he overenthusiastically lunged with his sword, piercing the cardboard armour of his opponent. The other assistant, or more strictly �Assistentin�, was Frauelein Graf, a rather buxom Bavarian girl who often turned up in national costume or �Dirndltracht�. This was always popular due to the low cut of her blouse.

French was taught by the excellent but very dry �Jake� Moseley. I remember often fighting to stay awake on hot sunny afternoons in French as he droned monotonously on, especially later during A Level in the �House� part of the school. This was where, in boarding days, the headmaster�s quarters had been. Although boring, �Jake� was nonetheless a very good teacher. Later, a female teacher (mistress!?) joined the school as a French teacher. A Frenchwoman, she had married an RAF officer during the war. Due to her extremely pale complexion, possibly an albino (she always wore dark glasses), she became known, somewhat cruelly, as �Medusa�.

The junior Latin master was �Streaky� Bacon, a rather eccentric, but very good teacher who always made Latin an interesting subject. He had planned to run a Greek O Level course which I intended signing up for, but this was kyboshed by him being involved in a serious car accident which removed him from school for a very long time. The senior Latin master was �Quilp� Harris. He was a rather bohemian character who never wore a tie, always an open necked shirt; at this time, this was very bohemian for a grammar school teacher. He also ran the school library and was something of a martinet. With him being single, we entertained �suspicions� about him, although it has to be stressed these were totally unfounded. They were enough however to prevent me taking Latin at A Level, since, as the only pupil wanting to do this subject in the Sixth Form, I was not keen on being closeted alone with him in his study in the House! A great pity, since I feel I would have enjoyed Latin much more than English, which I took in its place.

Early English was taught by Mr Gregory, but later we came under �Chippy� Woods. �Chippy� had served in the Royal Tank Regiment during the war, serving in armoured cars, and frequently regaled us with tales of the sights he had seen in Egypt and Italy, following in the steps of the likes of Byron and Shelley on their Grand Tours. We gained the impression that his war had been more of a Cook�s Tour than a series of military campaigns. When the annual school play was Rattigan�s �Ross� one year, TE Lawrence�s uniform was provided by �Chippy�. As stated earlier, �Chippy� was virtually addicted to Zubes, constantly sucking at one; I suspect that this was due to his heavy smoking.

History was the province of �Len� Morgan, the extremely eccentric, if not downright batty, Deputy Headmaster. School folklore had it that he had been passed over for the post of Headmaster in favour of �Roy� Wiltshire. He was one of the masters who permanently wore a gown, his in tatters behind him, looking like a black rag he had scrounged and wrapped around himself. He was very scathing of politics, often declaiming that in Pontypool, if Labour put up a monkey at the General Election, the people would vote it in. He was given to dramatic gestures such as, when teaching about Cobden and Bright and the Anti-Corn Law League, he would whirl an imaginary �key to the Free Trade cupboard� around his head. Another time, when dramatically talking of the Battle of Rorke�s Drift (little known at this time, pre- �Zulu�), he did an enthusiastic bayonet charge down the classroom, using one of the hooked poles for opening top windows.

Less �pupil-friendly� was the music master in the First Form, �Sexton� Blake. Not a fully qualified teacher, in addition to music he taught first formers geography (in the same way that �Maxie� taught Religious Instruction). On his entry into the classroom, all chatter ceased immediately and every pupil �sat to attention� in his chair, arms forced painfully over the back and downwards. Once he was settled in his desk, he would give the order �at ease!� and we could relax (a little). On our second day at school, he gave us homework � an essay on �Communications in the Eastern Valley�. A couple of days later, on returning our books, he called me out the front; �Skuse, how DARE you write an essay on communications in the Eastern Valley and omit Pontypool Road Station! Bend over!� At this point he gave me six with �The Dap�, a great West Mon institution (another Section 47 Assault). Actually, �Sexton� was one of the very few teachers I would say who was vicious to boys because he could be, and he enjoyed it.

Sciences - Physics, Geography, Chemistry and Biology, were subjects to drop as soon as possible after 2W, less Biology, since a science was needed at O Level, and Biology was the �least scientific�. I never had a leaning towards the Sciences and, while I could grasp the basics of Physics and Chemistry, once numbers and equations entered the stage, I was lost.

Unfortunately, Maths couldn�t be dropped. Initially, my Maths master was �Noddy� Jones with whom I never got on, but do sympathise with. He could never understand why an apparently normal, intelligent person could fail to grasp the simplest concepts of Mathematics. On several occasions, whilst trying to drum something into me, he would rap me on the forehead with his knuckles to emphasise the point (yet another Section 47 Assault). He wailed to me in frustration several times: �but if you can do Latin, you can do Maths, it�s very similar� (oh, really!).

Much more pleasant, but equally unsuccessful at teaching me even the basic rudiments of Algebra, Arithmetic and Geometry, was �Major� Williams �Major� was an interesting character who had been awarded the MBE during the war for his work on the PLUTO fuel supply system for the Normandy campaign after D Day. Towards the end of the O Level syllabus, he introduced the class to Calculus, �out of interest�. On announcing this intention, he remarked to me; �Skuse, you just read a book while we do this�. The last time I saw him, he was slumped over his desk in agony in front of us. One boy timidly asked if he should get an aspirin from the School Office, �I need more than an aspirin boy� he replied through clenched teeth. After this heart attack, he never came back to school and I often speculate if it was my fault.

Another disastrous subject for me was woodwork and technical drawing, under the aegis of the tiny �Stumpy� Hall. These lessons alternated, the technical drawing being used to design the next project � pencil sharpener, boot scraper, nothing too complex, but still beyond my ham fisted talents. Using the 2H pencil we were expected to produce extremely fine lines. One day, as he strutted up and down the rows of drawing boards, he paused by mine, grasped a hair on my head and, saying this was how fine he wanted the lines, pulled at it. Unfortunately it took several attempts to pluck a hair (yes, a Section 47 Assault) and, having succeeded, he examined it and said, �Er, no, not like this one, finer!� Alas, my mother had to make do with a boot scraper and pencil sharpener, neither very symmetrical, not the smart furniture others produced. Again, another subject to drop as soon as possible. As a postscript, later, the army forced me to do a draughtsman�s course; this was every bit as unsuccessful as my school experience and I lasted six months before being given another posting.

.. �Dressing table in mahogany, with teak veneer by RM Rosser� ..

(From the 1967 edition of �The Westmonian�)

.. �Draughtsman�s Pencil sharpener by L Skuse in beech and sandpaper� ..

Art was another non-subject for me. The art master Mr James was another exponent of The Dap. In his studio, he had one hanging on the wall with, artistically (of course) painted on the sole, �The Persuader�. A total inability to draw was something of a handicap to me in this field, but fortunately it wasn�t taken too seriously as a subject. My most ambitious project was a pottery dish. I intended laying out a fish in white slip on the black background, but ended up swirling it around to form a pattern. My mother faithfully kept this for years, until apparently one day, it just disintegrated; not a problem Crown Derby or Wedgwood suffers from.

Music was similarly regarded. Although non musical and tone deaf, I did, in the first year join �Noel� James� school choir, as an alto. The culmination of the year was a tour of local Old People�s Homes, singing carols. I don�t know what they thought of us, but nobody openly complained. In later years, people have simply refused to believe I was a chorister!

The Science I did like was Biology, taught by �Long Tom� Rosser. He was a very ebullient master about six feet four inches tall, and to see him get in and out of his Morris Minor was a treat. Generally jolly, when pushed too far, he had a dap the size of a cricket bat (or so it seemed), which he would wield with all his might. Unfortunately, although I needed a Science subject at O Level, even Biology eluded me, partly no doubt due to my very poor diagrams (in Chemistry and Physics there were stencils with various symbols and equipment, I never found a stencil with which to draw the reproductive system of a rabbit, or the structure of a paramecium). He was fairly easy to �get going�, one boy �innocently� reporting that he had read in a newspaper of a girl claiming to have become pregnant from sperm left in a bath. �Long Tom� roared on for several minutes, describing the arduous journey spermatozoa had to undertake, and how conception was impossible under the described circumstances; it took us successfully up until the bell rang.

There were a variety of extra-curricular activities, some of which I got involved in at various times. The Local History Society was a good one, with regular bus trips to such places as Caerphilly Castle and Tretower Court. Then there was a brief flirtation with the Model Railway Society, and the Chess Club. I actually started out quite well, representing the school one season, culminating in being picked for the county team (at that time, Monmouthshire). Unfortunately, through sheer overconfidence, of twelve boards, I lost the only match, never being invited to play at county level again, although I continued playing for the school. I did once get dragged into being on the school debating team for an inter-school competition held at the old Pontypool Settlement; I can�t remember how we did.

School meals were pretty standard for the era; lots of stodge and gristle, and lumpy custard, and of course, fish, mashed potato and tinned tomatoes on Fridays. Occasionally I would bully my mother into making up sandwiches, which were eaten in the �Day Rooms�, a wing of the building under the library, and along one side of the quadrangle. There were no tables and chairs, lunch being eaten around the walls. Of course, there was still daily milk then, but given the physique and health of the pupils it was clearly a waste of money which could have been spent elsewhere. In the Sixth Form, I got involved with Dave Pearce and Stuart Gironwy Jones, �SG� in selling crisps and cheese biscuits to pupils to consume with their milk, definitely �non-Jamie Oliver! A bonus of this was that we brought the milk into our stock room and took it out for milk break; I used to get more than a third of a pint a day!

Breaks were spent in the quadrangle or up the field at the back of school. Smokers used to gather in the old quarry there for their illicit puffs. The quadrangle was the venue for touch rugby, played with a rolled up rough book secured with sellotape. Since tackling on tarmac was impractical, the �ball� had to be passed as soon as the player was touched, hence the name.

Eventually A Levels came and went. Since I managed to stay in the �W� stream, I took O Levels a year early (pupils went straight from 3W to 5W), this gave me the opportunity to stay on a year to improve my grades which had been insufficient to gain a university place and still remain �on target� age wise. As I didn�t particularly want to go university anyway, this meant that that final year, forced on me, was a bit of a waste of time, especially as for all three subjects (English, German and French) there were completely new set books to get to grips with, unlike for example, Maths or Geography, which are fixed subjects. Thus I did slightly worse the second time round, but at least I was finally freed of pressure to go to university. I eventually entered the army, via Burton�s Gold Medal Biscuits, to do a full thirty five years.

Notwithstanding the fact that I never got to university, I thoroughly enjoyed my time at West Mon, and feel privileged to have had the good fortune to have received a grammar school education which has always stood me in good stead. I deeply regret the passing of the Old West Mon; I mean they have girls there now!

.. Serve and Obey!� ,,

[1] �The apes are racing through the forest; they are looking for the coconut, who has swiped the coconut?�